I wanted to reflect on something that I observed recently both in my own class and in the class of another teacher. Setting makes a difference. As teachers we all know this, but sometimes we assume that our only options exist within the four walls of our classrooms and that is simply not the case. I'm going to relate 3 observations from the past few weeks that highlighted how effective a change of environment can be on student learning.

Two weeks ago I took my class to a local cafe to do our lesson. We were studying a particularly dry poem from the 18th century and my (admittedly weak) curricular link was that the coffee house was invented in the 18th century so we had to do some "research". In truth, the students just completed a lesson that they would have completed in the classroom but it was a well needed change of scenery. The result was that the kids took their tasks much more seriously than I believe they would have if they had been back in the classroom. The environment in the cafe was mellow and comfortable and as they worked we chatted about how many discussions and breakthroughs happen outside the classroom and in informal environments. To be fair, I had carefully planned the lesson, structured the activities purposefully and made up the groups ahead of time, but I know that the results were far better than the same activities would have been in my regular classroom.

This past week we went to the graveyard to study another poem (this activity comes directly out of the Literature 12 IRP) but again, the change of environment worked to enhance the experience and overall effectiveness of the lesson. In this case, the setting of the lesson was directly related to the learning objectives. For this class I also added another component to save time. The bus ride to and from the graveyard takes approximately 15 minutes so we used a "flipped" approach where I made an 8 minute video to cover the introduction to the lesson so the transport time was used effectively and the students were briefed for the lesson while I was driving to the site. During the return trip students were asked to jot down notes for a final reflection or "exit slip" so I could assess their learning.

Finally, on Friday I was working with a math 9 class that was completing a lesson in the foods lab on rational numbers. For a more detailed breakdown of the lesson itself please see the blog of a teacher who did this lesson previously. Afterwards when the math teacher and I were debriefing the lesson I asked him if he had noticed a difference in the engagement of the students compared to more of a "stand-and-deliver" model in the classroom. What he said was that while he certainly felt that the activity of making the food increased the engagement the students, he had tried active and hands-on options in his class before and he felt the change of setting (different room/different adults involved etc.) had an even bigger impact on the focus of some of his students. He went on to say that in his P.E. classes he could see a difference if he had the same P.E. class play a game of soccer in the gym vs. outside on the field vs. downtown in the city's indoor soccer facility. He was amazed how differently the same students involved in the same activity could react in different environments.

All of these observations have got me thinking about how we really should be looking at ways to break down the walls of the classroom. At the high school level especially we have big obstacles such as curricular and timetabling constraints. However with possible huge changes coming our way (see Darcy Mullin's blog) I think now is the time to start looking at throwing the original model out the window. Creating freedom for learning outside the classroom and outside the school building should be a priority. I was able to take my Literature 12 classes on these trips because of a number of factors: I have a class-4 drivers licence, my vice-principal drove my students who we couldn't fit on the bus, I work at a school that has a bus, and I am comfortable enough with technology that I could make a video (which I was able to show on the bus because it has a TV and DVD player) to make up for the class time we were missing in transportation. This trip would be very difficult (if not impossible) for many high school teachers and that needs to change. However, while we are waiting for things such as curriculum to be reduced and timetables to be altered, teachers can still do creative things outside the classroom that are less intensive (such as taking classes outside, planning field trips within walking distance, or using the gym or foods lab etc.) but it really is time to start looking at breaking down the structural barriers at the high school level so our students will benefit from opportunities like those mentioned above (and so much much more). There are many people already thinking this way (see this awesome blog by David Truss for a start).

These personal observations in recent weeks, combined with the thoughts of a number of my fellow educators have led me to the conclusion that our entire education system needs a complete change of scenery.

Sunday, 9 December 2012

Sunday, 11 November 2012

In Memory

|

| Don McGourlick (age 20) |

For the first time since I can remember I am not attending a Remembrance Day Ceremony this year. My grandfather (who was a WWII veteran ) passed away on Oct. 26th, and this will be the first time that I haven't called him on Nov. 11th to personally thank him for his service. I didn't even go to our school ceremony on Friday, which as most teachers will tell you is always a bittersweet experience as we recount the horrors and sacrifice of war and yet are filled with hope for the future by the sincerity and respect that our students demonstrate. My grandfather never attended Remembrance Day Ceremonies. He never spoke of his experiences in the war to me. It was also his wish that he not have a funeral service, so instead of going to a ceremony this year, I'm going to write this post at 11am. Forgive me for its lack of polish.

|

| My grandfather and the rest of his crew (pilot not in photo) |

|

|

| In front of the cenotaph in Moose Jaw SK (with his name on it) |

Of course the man in the above story is not really the man I knew as my grandfather. When he recently passed away, I was working on writing his obituary and I had to ask my grandmother a few questions. She half jokingly said "Well I can read you his first obituary if you like". I know she wasn't serious, but what struck me is how little use the obituary of a 22 year old would be in comparison to the life of someone who has lived to be 91. How much more of his life happened over the next 69 years, and how short his 22 year old obituary was! I'm realizing now (funny how clarity comes when you are writing) that this blog isn't just a tribute to what my grandfather (and so many many others) did during the war, it is really a tribute to the life that he lived after he returned. After the war my grandfather had 2 children (and 4 grandchildren). He returned to university. He became a pharmacist. He lived in many places in Canada and overseas. He flew with Search and Rescue in the lower mainland. He was married to my grandmother for almost 69 years.

For my part, he was a kick-ass grandpa. My memories of him are of hockey rinks every winter in our backyard, of his "workshop" in the basement where he let us play around with everything from construction supplies to paints and clay to musical instruments to slingshots. I remember numerous fishing trips when I was home "sick" and I remember him picking my brother and I up after school in his VW van with a fridge full of chocolate bars. He could shoot a gun, build the best tree forts ever and recite classic poetry by heart. He taught me the importance of both creativity and work ethic. His impact on my life has been profound and I think despite everything that he went through, the greatest tribute to his life is that all four of his grandchildren (who are well into their adult lives) were present at 2 in the morning when he passed away. So I will write today to honour my grandfather, and what he contributed to my life, but also use his life to respect those men and women whose obituaries really were written when they were so very young. Four members of my grandfather's flight crew never had granddaughters who could reflect on their lives, and all the soldiers on that cenotaph in Moose Jaw were denied so many future experiences. Of course this is just a tiny tiny fraction of the lives that we have lost in so many wars. It is actually my grandmother who has reminded our family many times over the past few weeks that we should be looking at my grandfather's death with gratitude for the time we actually had. We are the lucky ones.

Saturday, 22 September 2012

What Divides Us

|

| On the way to Vancouver |

The result is that we have students who can’t afford to go.

I’m lucky that I work in a (relatively) small school where I know most of the kids, and if I don’t, there is likely another staff member that has a connection to them. If I see a student that showed initial interest (came and got a permission form and parent letter) but never ended up paying the money, then I feel comfortable discreetly asking them if there is a reason that they changed their mind. Some kids are extremely adept at covering up and quickly provide a reason such as they have to work, or they have other commitments. Sometimes these stories are authentic, but I know there are always students who lie because they are embarrassed to admit they simply don't have the funds. I spoke with a number of students this year who owned up to not having the money. I was able to convince them to come if we waived their fees but the conversation was obviously awkward and uncomfortable.

When I was in grade 10 my school offered a three day hiking trip to Mt. Robson for all students in my grade. I went to the initial information meeting (as did most of my classmates) and immediately got excited as the teacher sponsors described everything we would experience. Later in the meeting came the cost breakdown. The trip was going to cost $90 in straight fees and each student would need hiking boots, an actual hiking-grade back-pack, a sleeping bag and food for three days. While I was by no means living in poverty, my mom was a single parent, and the $90 plus new hiking boots, sleeping bag, back-pack and other expenses just weren’t going to be affordable at the time. I started convincing myself that the trip wasn’t such a big deal. I didn’t like hiking much anyway…I was too busy…I would miss too much school…the whole trip was going to be lame….except I knew none of these were true. It was going to be an awesome trip and many of the grade 10s (including all of my closest friends) were definitely going. I never went back to the next info session and I tried to put it out of my mind.

I'll never truly understand why we equate lack of money with inferiority and shame but there was no way I was going to admit to anyone that I couldn’t afford that trip. I was absolutely mortified when a teacher approached me and asked why I had stopped attending the trip meetings when I was so obviously excited initially. She asked me point blank if money was the issue and I (never having the skill of lying on the spot) admitted it was. The teacher explained that the school would cover the $90 and one of the PE teachers would lend me a set of used hiking boots and they would round up the rest of the equipment. I did go on the trip and it ended up becoming one of my favourite memories of my high school experience-not just grade 10. The trip was so memorable that it spawned a lifelong love of hiking and led to other adventures including the West Coast Trail and the Bowron Lake chain. When my own son turns 12 I am taking him and my husband up Mt. Robson. The trip that I couldn't afford turned out to be life-altering.

Talking to students who can’t afford to pay for something always reminds me of that experience. I can see them hesitate about whether or not it is worth it to tell me the truth. I can see that they truly want to participate in the activity but accepting charity is awkward at best and most of the time downright embarrassing no matter how gently I try to make the offer. I also know that their parents are embarrassed as well. No loving parent plans to deny a child the experiences and opportunities that his peers are given. No parent wants to tell a child she can't provide something her child deserves to have. When my mom found out that the school was going to pay for the trip and I was going to borrow second hand hiking boots she was devastated, and then trapped by the decision to either accept the help or deny her daughter a great experience. I’d also like to point out that poverty does not equal laziness or poor character. Yes, we have families in our school who have never paid a cent of school fees, but chances are they aren’t living the high life from the money they are saving by cheating the school system. Chances are the majority of them are struggling everyday to make things work for their families and it could be any number of circumstances that have put them in a current position of need. I will speak for the students who couldn’t pay for this particular trip. They are inspiring, hardworking and ethical young men and women. Their character is a testament that their parents have succeeded in the ways that count the most.

We cannot forget that it is possible for someone to be working as hard as they can every day and still not have enough. Some parents may be struggling with substance abuse or mental illness and the last thing we should be doing is making their children pay the price. These are the students that need these opportunities the most and we must continue to find ways to provide them; education must continue to be the great equalizer. Every student should have access to amazing drama performances, trips to the wilderness, participation on sports teams or in specialized programs. Financial circumstances should never separate a child from experiences or opportunities that will enrich their lives.

Saturday, 23 June 2012

To The Finish

|

| Yearbook pic of the 2 of us during the race (we did have colour photography back then!) |

The ancient grainy photo to the left captures me during our school's annual "Milk Run". I clearly remember the beginning of the race when I lined up with the massive crowd of restless students behind the starting line. As I waited nervously my basketball coach Mr. Henly came up beside me and asked if we could run together. The two of us often went jogging so I didn't have an issue, but I was aware that it might be a struggle to keep up with him during a competitive race. The starter's gun went off and the two us set off at what I would describe as an uncomfortably quick pace, and I was instantly aware that it would be difficult for me to maintain our speed, even for a race as short as the 3km route. I was a decent athlete in high school, but team sports were my thing and I had never really excelled at track. We were passing all sorts of "runners' though and I knew we were really flying when we passed one of the top female track athletes in the school. About halfway through the run I knew I was in serious trouble. All the usual cliches apply here: my lungs were screaming and my legs were burning. The remainder of the route was basically flat but any runner knows that a kilometer and a half can seem like a thousand when you have pushed your body beyond its limit. Through it all Mr. Henly kept up a steady chatter of encouragement. I was breathing too hard to offer any comments in return.

|

| Bird's Eye view of the end of the race course |

"I can't," I panted, "I'm done. You keep going."

He wouldn't listen: "Nope, come on, you can make it."

I was now becoming extremely angry. I was furious with myself for not being able to continue. I was embarrassed that I was quitting, and I was especially upset that I was letting him down. I also felt he was making it worse because now I was costing him important seconds on his own finishing time. I begged him to just keep going and to leave me alone, but he continued to stand there. My frustration was overwhelming. What was he doing? Why was he just standing there making an already humiliating situation even more painful? "Come on," he urged again, "you can do this".

No. I couldn't. I was done. And then I did something that embarrasses me to this day. I glared at one of the adults I respected as much as anyone else in my life and spat out, "What the hell does it matter to you anyway?"

At this point I'd given him every possible reason to walk away. I was angry, I was disrespectful, and with my last comment I'd certainly made it personal. He could have left me at that point and no one (including me) would ever have thought he had made the wrong decision, but he didn't. He just looked at the ground and said quietly, "Look Naryn, walk if you have to and I'll walk with you".

Whether I just gave up on the idea of getting him to leave, or whether I had gotten my wind back by this time, I slowly began to walk, and then jog again, and the two of us rounded the parking lot and finished the race. I actually tried to out sprint him over the last 50 metres which he found amusing while finishing the race just slightly in front.

I was confused for a long time about why he didn't just keep running once I had stopped. I had appreciated him running with me during the race but it made no sense for him to stay behind once I had quit. I can honestly say that it wasn't until over a decade later after I became a teacher, and after I became a mother that something dawned on me. I realized that he couldn't have cared less about how well he did in the race. It was never about him. It was always about me. His number one priority was that I finished the race. As a teenager, you really think that everyone views the world the way you do, but now I understand. Now it all makes sense.

So here at the end of another school year I find myself in the shoes of Mr. Henly. I have students that are driving me crazy because they are so close to finishing and yet they have stalled. It's also extremely frustrating that the more I try to encourage them to finish the more angry and confused they are about why it is bothering me so much that they are going to fail. In my mind all I am doing is bending over backwards to help them and all I am getting in return is attitude. In their minds, it would be a heck of a lot easier if their teacher would at least give them the dignity of failing alone, and not add a guilt trip on top of it.

But because of that day so many years ago, I am certain that they aren't quitting right now because they desire failure. I know they are honestly frustrated because they aren't having success and now they feel they are letting me down too. Their anger is created from their own inability to just finish, and it's very possible they won't understand my motivation as their teacher for many years (if ever). Do students have the right to fail? Absolutely. However when I have kids who have hung in all semester (with so many other obstacles in their lives) and who now for whatever reason just can't seem to take those last few steps, I will remember the teacher who stood stubbornly beside me that day and said, "I will not give up on you." I will stay with my own students until they are able to finish the race. I too will stand beside them and say, "Walk if you have to, I'll walk with you".

Saturday, 16 June 2012

Teaching the Teacher

|

| Playing the guitar in class on Friday |

|

| My son playing his new guitar |

Another student in my class has a certified obsession with zombies. I kid you not, if a zombie apocalypse was to happen (and it could happen) this young man would be organizing the survival plan for the human race. Through our discussions early in the semester he managed to convince me that a comprehensive knowledge of zombie lore was a key component to a well-lived life and he offered to supply the resources I needed to improve my understanding. His reading suggestions included "World War Z" and "The Zombie Survival Guide" by Max Brooks and he recommended viewing the first 2 seasons of "The Walking Dead" television series as well as numerous zombie movies. I started by reading the Max Brooks books and simultaneously watching "The Walking Dead". (For those interested, Season One is available on Netflix).

|

| Mandatory reading |

The truth is that my life has been enriched by the fact that I have known these two boys. The message when it comes to building the community in the classroom is that we are truly better if we see value in others and allow our lives to be impacted by them in a positive way. My son and I are now playing the guitar together because of the first student, and the second student has proven to me (against expectations) that very intelligent social commentary can come from the horror genre. My next plan is to donate blood because of the discussion that came up in class about the experiences of another student. Again, something completely out of my comfort zone, but I know that I will have the experience because of the influence of the student, and I will now never forget how he changed the course of my life in a small way.

The five months that I have spent with my students hasn't just been about me teaching them Literature 12; it has been about the collective exchange of the strengths and passions and energies of everyone in the group. The hope is that students will understand that everyone has something to teach them and important lessons and experiences can come from almost any source if you are open minded enough to let yourself realize it. I also want my students to recognize that our "teachers" are not just those in positions of power or influence over us, but that every member of the class (and our society) has something valuable to contribute. What better way to honour and respect our students than to send the message "I can learn from you as well"? We need to be open and curious towards new experiences and try things out of our comfort zone. Of course there is nothing directly related to zombies or the guitar on the curriculum for Literature 12 but when members of the class are open to accepting and appreciating and learning from each other then a more productive learning environment will naturally occur. (For the record, both of these students have been incorporating their passions into the class throughout the semester, and both will use them in their final projects for the course). I don't just want my course to be about learning classic literature; I want it to be an organic experience with everyone learning from each other and connecting to the themes of great literature throughout. If I want them to truly value the passions and experience of others, then as the teacher I must also model my willingness to learn. Giving someone else the power to influence our lives makes us vulnerable, but it is essential that we share how our own lives are enriched when we give others the power to teach us.

Saturday, 9 June 2012

System Error

|

The man in the picture, Jordan, will tell you that his difficulties in school began in grade 1. Sitting still was an issue, and he was constantly disrupting the class by trying to talk to his neighbours. He was regularly reprimanded for speaking out was often sent to the office for his inability to focus. He swears he had no intention of deliberate defiance, but he was uninterested in school in general and he kept getting distracted.

Jordan was extremely social and very athletic but these skills were only a detriment in his elementary years. It took seven years before his first highlight when his teacher assigned an oral presentation on a character from a Greek myth. He created a full costume and wrote a script and shocked his class with an amazing and dramatic presentation. It was the only "A" he received in his entire elementary or secondary school experience.

Grade 8 brought high school and still more struggles. Class was no less boring than in elementary school but at least he changed teachers and classrooms every hour. Then in grade 9 his home life officially fell apart and because of family issues he ended up living in 3 different communities and attending 5 different high schools. Regardless of the city or the school, the classes remained the same. He walked in, sat down and listened to the teacher talk. He filled in worksheets and struggled to stay awake. It took him an extra year to graduate from high school (he failed Biology 12), and throughout those years his only passion was hockey. Once he finally graduated he decided he'd had enough of school and he travelled around playing Jr. Hockey for 3 years at both the Jr. A and WHL level.

Jordan's experience in Jr. hockey earned him the attention of some university hockey programs and despite his very low high school grades he was offered a scholarship by the University of Ottawa. When he returned to his high school to pick up his transcripts a counsellor warned him that it was unlikely his grades would gain him admission even as a mature student, but the university made an exception on the condition that he maintain a reasonable academic standing from that point on. Once Jordan completed his first semester at the university he discovered something that completely changed his perspective on education. He learned that there was a difference in the way professors evaluated their courses. Some courses weighted heavily on written exams, others put most of the emphasis on papers, and still others put heavy emphasis on discussion, seminars, projects, and presentations. Jordan knew that he truly struggled with traditional written exams. He also had difficulties with writing, but essays and term papers were slightly better because he could work on them ahead of time and take them to a professor or TA for feedback. He also discovered that he absolutely excelled at oral presentations because verbal exchange was a definite strength. In Jordan's words: "I am a thousand times more effective with oral communication than with written. I simply cannot write the way I can speak." He started getting positive feedback on his presentations from his classmates and professors. His style and passion resonated with people.

By his third year in Ottawa Jordan was choosing his courses based exclusively on the method of evaluation. He went to professors ahead of time and asked to see course outlines. If a course evaluation was weighted heavily towards a timed exam then he avoided it. Papers were better and courses with any component involving verbal expression were his first choice. He completed his Bachelor's Degree in Criminology and graduated with honours.

Then came law school. Unfortunately the number one criteria for entry into law school was the LSAT which was exactly the type of test Jordan struggled with. He studied and took courses to prepare and ultimately survived the exam, however he was frustrated because he knew he possessed skills that would benefit him as a lawyer yet were not measured by the LSAT itself. After rejections from 9 law schools he finally received an acceptance letter from the University of Ottawa and after completing law school (while playing for the University of Ottawa's varsity hockey team and also being an assistant coach) he wrote the bar exam and received an articling position with a firm in Victoria.

Once he became a practicing lawyer, Jordan's success was quick and notable. Within a year of being called to the bar he was running his first jury trial. Just 3 years into his career he was made partner by the largest criminal law firm in B.C. He is now in his fourth year and has run trials involving the most serious charges in our justice system. He faces incredible stress on a regular basis and works with some of the most difficult citizens and situations that exist in our society and yet he is successful. The reason I find Jordan's journey so fascinating is that none of the traditional indicators for professional success (such as high school grades, provincial exams, and admissions tests such as the LSAT) accurately predicted his future capabilities as a lawyer. People who were far more engaged and successful in elementary and high school, and who scored much higher on standard assessments would never be able to handle the requirements of his career.

What's even more interesting about Jordan's story is that the skills that have benefited him so much as a lawyer (mainly his public speaking and presentation skills, and his ability to relate and connect and work with people) so rarely did him any good throughout the majority of his years in the education system. What good is the ability to communicate verbally if you only sit in a desk and listen to a lecture? Who cares how well you argue when teachers reward students who sit quietly and listen passively? How important is your ability to relate to others if everything in the classroom is completed individually? When Jordan was finally successful in university it was because his number one focus was on how he would be evaluated which he prioritized even above the subject of the course itself. Imagine his educational experience if he could have taken the subjects he was the most naturally interested in, and then been given a choice of how to demonstrate his learning.

Jordan is an intelligent human being with obvious strengths and abilities, however he is someone who was not a traditional "academic". He would not have been a person expected to continue on to post secondary and later law school, and yet the reality is that his strengths make him almost perfectly suited for a career in a courtroom. Jordan points out that, "our school system only values one style of learning. It is heavily weighted towards students who excel at essay writing and written tests, when there are other ways to learn that are equally valid". As educators we must make it a priority to provide more ways for students to connect with their strengths and be assessed in ways beyond written response. We must provide more varied opportunities in our classrooms for students to both engage with the material and to express their understanding. Jordan was successful because he was finally given some choice in university and he learned to navigate the system to his advantage, but if it wasn't for hockey he would never have considered university in the first place. Most students would not return to formal education after 12 years of frustration. How many potential success stories have we lost because students were unable to use their natural abilities and passions to their advantage for most of their educational experience? A path that suits each student's strengths should be available in our schools and we must strive to make it clear and well "marked".

Once he became a practicing lawyer, Jordan's success was quick and notable. Within a year of being called to the bar he was running his first jury trial. Just 3 years into his career he was made partner by the largest criminal law firm in B.C. He is now in his fourth year and has run trials involving the most serious charges in our justice system. He faces incredible stress on a regular basis and works with some of the most difficult citizens and situations that exist in our society and yet he is successful. The reason I find Jordan's journey so fascinating is that none of the traditional indicators for professional success (such as high school grades, provincial exams, and admissions tests such as the LSAT) accurately predicted his future capabilities as a lawyer. People who were far more engaged and successful in elementary and high school, and who scored much higher on standard assessments would never be able to handle the requirements of his career.

What's even more interesting about Jordan's story is that the skills that have benefited him so much as a lawyer (mainly his public speaking and presentation skills, and his ability to relate and connect and work with people) so rarely did him any good throughout the majority of his years in the education system. What good is the ability to communicate verbally if you only sit in a desk and listen to a lecture? Who cares how well you argue when teachers reward students who sit quietly and listen passively? How important is your ability to relate to others if everything in the classroom is completed individually? When Jordan was finally successful in university it was because his number one focus was on how he would be evaluated which he prioritized even above the subject of the course itself. Imagine his educational experience if he could have taken the subjects he was the most naturally interested in, and then been given a choice of how to demonstrate his learning.

Jordan is an intelligent human being with obvious strengths and abilities, however he is someone who was not a traditional "academic". He would not have been a person expected to continue on to post secondary and later law school, and yet the reality is that his strengths make him almost perfectly suited for a career in a courtroom. Jordan points out that, "our school system only values one style of learning. It is heavily weighted towards students who excel at essay writing and written tests, when there are other ways to learn that are equally valid". As educators we must make it a priority to provide more ways for students to connect with their strengths and be assessed in ways beyond written response. We must provide more varied opportunities in our classrooms for students to both engage with the material and to express their understanding. Jordan was successful because he was finally given some choice in university and he learned to navigate the system to his advantage, but if it wasn't for hockey he would never have considered university in the first place. Most students would not return to formal education after 12 years of frustration. How many potential success stories have we lost because students were unable to use their natural abilities and passions to their advantage for most of their educational experience? A path that suits each student's strengths should be available in our schools and we must strive to make it clear and well "marked".

Friday, 1 June 2012

Do Not Go Gentle

|

| Students film a re-enactment of a poem using supplies from the candy station |

This week students have appeared to be completely uninspired. We still have another 12 days of classes (and then exams) but we all have "summer on the brain". Let's face it, we live in Penticton. The weather is spectacular and it's hard to justify being inside at all. To top it all off, the grads were having their big grad camp out this weekend and there were rumours that most of them weren't even going to be in school for a good part of the day. What's a grade 12 teacher to do? If the students don't care why should I bother? Luckily I've been physically (and virtually) surrounded by a number of educators who refuse to see apathy as a "student" problem. Inspired by so many others who were refusing to give in to the "dying of the light" I decided to go for it. If only 2 students showed up for class on Friday, so be it. In order to review our unit on the Romantic Poets I took the QR code idea and linked it to various video clues. The QR code clues and puzzles were then combined with a creative component where teams had to complete 10 of 14 tasks using creative methods. I then added a final challenge directly inspired by the brilliant "Mullet Ratio"lesson which I had learned about via twitter.

Stage One of the challenge was based on the QR codes. The QR clues were mostly linked to basic recall questions but I asked different staff members to let me take short videos of them reading out the clues. The students really appreciated the variety and participation of those teachers. Stage Two was the creative component. The creative challenges involved various tasks including dance, art, music and technology. Students had to re-create key elements of the poems and make connections between them in creative ways. Every team had a flip camera so they recorded their activities and explanations on video (because there is no way I could track all the teams at once when they were all over the building). At the end of the challenge every team handed in one video camera and one puzzle sheet where they had recorded the video clues and decoded a puzzle. (Thanks again to Pernille for the webinar on using video cameras in the classroom).

|

| "Rapping" key lines of a poem with a beat from the keyboard |

Once students had completed the QR code puzzle and the creative challenges, they had one Final Challenge to finish. The challenge simply asked students to connect any poem in the unit in any way possible to the topic of "mullets". We made a "Wall of Epic Mullets" on the board and all the groups had to add their ideas to the wall. Points were awarded for connecting knowledge of the poems to the concept of "mulletness". I admit that the mullet idea was really just about the novelty. Kids thought it was funny and they certainly had to think outside the box to connect 200 year old poetry to the concept of a hairstyle. Luckily mullets DO give you lots to work with if you are used to thinking in a creative and abstract way. We put up some pictures of epic mullets on people like Chuck Norris, Jaromir Jagr and George Clooney to add inspiration.

The lesson was a definite success. Students who had been starting to tune out were running from QR code to QR code and from challenge to challenge. My absolute favourite moment was a student in full sprint down the hallway yelling "Searcy! We found the last code!!" While I wish he hadn't yelled quite so loudly, I have to say that having that particular student show that much enthusiasm could only be described as a triumph.

|

| Drawing key themes using window writers |

There are two things I will always remember about today. First, I will remember the efforts of my students. They showed up and they bought in. Despite the fact that it was 2nd to last block on the Friday of grad camp out, they were running around, drawing, rapping, sculpting and arguing about how to connect old poetry to mullets. Attendance was excellent, and every group was still working when the bell rang to end the class. I spent most of my time laughing at their quirky creativity and frantic efforts to find little coloured bar codes hidden around the school. I was reminded once again about why I love working with teenagers. As students ran past me down the hallway or came up with a creative connections I kept thinking that the whole thing was so worth it.

|

| Making connections on the "Epic Wall of Mullets" |

The most memorable lesson I will take from today however, is the power of the inspiration of others. Eight different staff members at my school helped me create video clues for the scavenger hunt. I was also able to draw from the examples of other teachers like Pernille and Scott and Russ who were using creative ways to keep their own students motivated. When I was personally losing momentum and thinking "What's the point? we're so close to the end anyway, there were other educators around me who themselves refused to stop pushing forward. Their efforts gave me the inspiration to keep trying new things. In times like this I believe our students need us to step up and prove that we do value their education and their time and that they are worth putting in that extra effort. As adults, we also need to model that we are able to push through fatigue and promote excellence even when we are the least motivated to do so.

Saturday, 26 May 2012

In the Real World

|

| Dave works on the chair while Elaine holds Tas in position |

The picture above captures the amazing team of Elaine (OT) and Dave (Technician) who have been adapting our daughter Taslyn's wheelchair and positioning devices for over ten years. Basically they (along with the rest of their small team) design and build mobility devices for most of the handicapped children in the Province of B.C. The work that these two do absolutely fascinates me (and I think they are tired of all my questions!) Basically Dave and Elaine's careers are completely based in collaborative, creative problem solving. They assess the individual needs of each child (spasticity, mobility, positioning etc.) and then the create an original design that will suit the needs of the child, and then they literally build it (on site) over the next few days. There is absolutely no textbook or design manual for the work that they do. Many of the most ingenious designs on our daughter's wheelchair have actually been created by Dave himself. From the beginning of their day to the end they are coming up with creative and individualized solutions. Their job is particularly challenging because as Dave says: "None of these kids play by the rules. There are no rules". Every child has unique demands so Dave and Elaine need to start fresh with each new patient, and because each of the children they work with has a handicap (or many) none of their bodies are "logical".

Flash forward to the experience I had today. Today I spent approximately 7 hours staring at a computer screen reading hundreds of essays written by students about the same 2 articles on the English 12 Provincial Exam. I found it interesting to think about the fact that it was so different from my very recent experience in the "real world" and yet, aren't provincial exams what we rely on to ensure our graduates are prepared for the rigour and accountability of life after high school?

|

The English 12 Provincial E-Exam Marking Committee (Good Times!!)Here is what I observed in the situation around the English 12 Provincial Exam |

- Students write the exam at the same time and they have a finite time frame (3 hours) to complete the exam

- All students write identical exam questions regardless of personal interest or background (the three key texts on the May exam were based on a) technology b) hockey goaltenders c) baseball )

- The exam is written completely out of context. The questions are simply "exam questions" and have no higher purpose (once the exams are read and the mark recorded the exams will eventually be discarded)

- Students write the exam independently

- Marking the exam is as uninspiring as the writing of it must have been

- The exam is worth 40% of a student's grade in English 12

- Students all write the exam under identical conditions (on a computer in a lab). During larger sessions in January and June, students also write in an exam setting such as the one below:

|

| Students at my school during January Exams |

In contrast, here is what I observed in the "real world":

- Many problems are often not solved on a set time line. For example we had a specific issue with my daughter's wheelchair and Elaine needed to let it "ferment" in her brain overnight. When we came back the next day she had a solution ready. If she had been required to solve it in a three hour limit she would have "failed".

- Most problems have more than one possible solution

- Problems can be solved with the input from more than one person. Elaine often jokes that she and Dave "share a brain". They are constantly consulting with each other, with other members of their team, and with the parents and the children themselves

- Problems change over time and what once worked may not work in the future and may have to be adapted

- Solutions just can't be "memorized" if you are always dealing with new issues and situations

- If an idea fails it just means you need to try another solution (our daughter's wheelchair has been altered many times because initial attempts were not successful)

- Real problems have a context and a purpose. Dave and Elaine can directly see the impact of their work and the actual people that they are helping. While their work is extremely demanding, they are directly able to experience the results and thus remain inspired and motivated

Now, I do need to provide a disclaimer. As a senior English teacher I must mention that I believe that the skills assessed by the English 12 exam (including reading comprehension, writing, synthesis, and original composition) are completely valid (and extremely important). I also believe that these skills should certainly be assessed in all students. The problem is in the way we assess those skills which completely de-contextualizes everything and (with the exception of the original composition section) leaves no opportunity for personalization or creativity. For the record, approximately 75% of the responses on the original composition section are also presented in a formulaic expository essay format (despite the fact that students are given freedom to respond creatively if they choose). The majority of the test leaves no room for individual interests and completely separates the skills from a real purpose, (and don't even get me started on the multiple choice section!). As provincial exams at the high school level go however, it is potentially superior to the rote memorization of trivia demanded by many sections of the Socials 11 and Science 10 exams.

Daniel Pink writes:

A

quick thought about the disconnect between how we prepare kids for work and how

work actually operates:

In

school, problems almost always are clearly defined, confined to a

single discipline, and have one right answer.

But in the workplace,

they’re practically the opposite. Problems are usually poorly defined, multi-disciplinary,

and have several possible answers, none of them perfect.

As someone who works with grade 12s I am constantly reminded of my responsibility to prepare students for their lives after high school. Therefore, if the main argument for provincial exams is that we are enforcing "standards" and "accountability" and "rigour" so that our students are prepared for the "real world" I think we need to think about what "real world" we are actually talking about. The real world I was in for most of the week had very little connection to the provincial exams that I marked today.

Friday, 18 May 2012

Gone Fishing

|

| A master at work |

The first student is a young man that I haven't taught since grade 9 (he is currently in grade 11). During his English 9 days he was one of my most frustrating students when it came to effort and work completion. While we had a good personal relationship, he would often refuse to complete written work and he absolutely loathed reading. There were many one-on-one talks, then eventual trips to the lunch hour homework room and finally meetings with his parents and admin as well as suspensions (for all of his courses not just English). I do remember his mom telling me about his love of outdoor activities including mountain biking, hunting, and fishing. At school however, he simply seemed to suffer through most of his courses.

|

| Catch #2 (before being released) |

|

| The now crowded dock |

Perhaps those were not accurate observations. Perhaps I was simply observing the students in contexts that played to their individual strengths, and when it came to confidence, skill, and tenacity they were actually both fairly equal. We all like to consider ourselves determined in the face of adversity, but how many of us put ourselves through situations day after day where we are unsuccessful? As an English teacher I observed each student over and over again in situations where one was constantly being rewarded and one was constantly being punished. What if we reversed what we valued in school? What if school was seven blocks of fishing a day and one block of an "academic" subject? Which student would have straight As and which student might be at-risk of not graduating?

Overall it was a wonderful class because we were able to observe the first student in an environment where he excelled, and could earn the respect of his teachers and peers. No matter what the context, it is always a pleasure to watch someone who is passionate about what they are doing. I was struck by how drastically different that 45 minutes at the lake was to what he faces every day in our school where class after class is a frustration. Just today at lunch I heard his name called (again) over the announcements for not attending homework club. It is actually amazing that he has hung in for this long. I wonder how student number two would respond if he was summoned to homework club at lunch and found a rod and reel waiting for him...

Saturday, 12 May 2012

Nothing Is Interesting If You're Not Interested

|

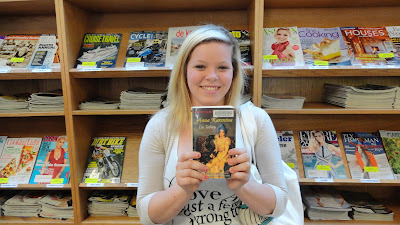

| Student with a copy of Anna Karenina |

On Friday a student shared with me that her grandmother had passed away, and since I had already been planning on writing a post about this particular student, I think it's a fitting time to write this. I taught the young lady in the above photo in my first semester Literature class, and her story is now added to the many experiences that continue to shape my perspective as an educator.

Please walk briefly back in time with me to Sept. 7th, 2011. It is my second day with my new batch of Grade 12 Literature students, and the epic Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf is on the agenda. It's a large class and they are shaping up to be a loud and energetic group. They are responding very enthusiastically to some of the activities involving modern culture and music, but at some point they will start to realize that a key component of the course is to read (!) some really old (and often dry) poetry. It is now the moment of truth and I hand out the first 6 pages of Beowulf. To be fair, Beowulf is long but it isn't that difficult to sell with its heroes, monsters, blood and gore; however, my strongest memory of that 2nd day of class is of the above student commenting (loudly enough for me to hear) as she finishes the first page and then flips ahead:

"Oh my God!! This is SIX PAGES LONG! The MOVIE would be shorter!"

I certainly realized at the time that this was not a good sign. While I appreciated the honest feedback, it was definitely going to be a long semester if 6 pages of poetry was too much for a student to tackle. Because of her negative response to the reading my first thought was that she was a struggling learner, as kids who dislike reading often fear length of text above all. If 6 pages of Beowulf was too much then comprehension was possibly a larger issue. I mentally lumped this student in with those who strongly disliked reading and therefore required extra encouragement, scaffolding and active options.

Flash forward to the end of the course in late January 2012 when this student was completing her final assessment. In the course students are given a number of options for a final assessment and one of their choices is a "Cultural Literature"project. "Cultural Literature" requires students to complete further research beyond the course. They must demonstrate an understanding of the skills taught in Lit 12 (critical literary analysis, awareness of style, technique, context, language etc.) and apply them to literature from their own cultural heritage. Imagine my surprise when this student chose the "Cultural Literature" option instead of a creative project or a final exam. I was even more confused when the time came for her to present her final project to me (students present their projects in a 15 minute live interview format) because what came next was certainly not what I would have expected. She began the interview by describing her choice to study Russian Literature for her project and then launched into a reflection on Tolstoy's "Anna Karenina." I almost fell out of my chair. Everyone knows that kids who don't like reading don't decide to tackle one of the lengthiest novels ever written.

Me: "Did you say Anna Karenina? You didn't seriously read Anna Karenina..THE Anna Karenina"?

Student: "Yes, (small sigh of impatience) that's what I said"

Me: Name a character in the book...besides Anna.

Student: "There's about fifty, but how about Vronsky, Levin, Stiva, Dolly..."

Yes, she had actually read it. My "reluctant reader" had polished off Tolstoy's massively complicated Russian classic. As the interview continued, she explained that her interest in Russian history and culture stemmed from the relationship she had with her Russian grandmother who lived in Penticton and had told her Russian stories since she was a child. Throughout her final project she had discussed what she was reading with her grandmother and had numerous conversations about her grandparents growing up in Russia and living under the reign of Stalin. I was suitably impressed when the student explained the difference between the Russia of "Anna Karenina" (which took place during Tsarist rule) and the experiences of her grandmother while Stalin was in power. Her grandmother's fading health at the time made the exchanges even more valued.

In reality, this student wasn't a struggling reader at all. She hadn't rejected Beowulf because she couldn't read it, she had rejected it because she didn't care about it. As a teacher, I hadn't done an effective job helping her discover the connections between Beowulf and her own life. It all came down to what was truly relevant in this student's perspective, and in this context it became obvious that 6 pages of Beowulf was too much effort, while 860 pages of Tolstoy was completely reasonable. I don't think I have ever had a clearer indication of the correlation between relevance and student motivation. Back in September after the student's initially negative response it was easy to consider laziness, low ability, or inability to focus as culprits when in truth she saw no purpose in reading Beowulf. I know there are many students who balk at reading because of legitimate learning difficulties, but in this case I had identified a struggling learner when in fact I was dealing with an unmotivated one.

My second semester has given me a chance to try and re-focus my instruction with the idea of relevance at the forefront. It has been considerably "messy" as I try to re-create project options and intros to lessons but the overall result will (hopefully) provide a more meaningful experience for my students, as well as a higher level of engagement and a deeper connection with the material. The experience has also reminded me that up until last year I always kept a sticky note on my desk with the following quote: "Nothing Is Interesting If You're Not Interested". That quote has been stuck to my computer over the past decade in countless classrooms in three different schools but somehow it got lost over the past year. Thanks to this student, it's now back on my computer monitor where it belongs.

Side Note: Another reason that 2nd day of class is still so clear in my mind is because later that day I recorded a video reflection. My only goal was to demonstrate how a teacher could use a flip camera to reflect (instead of having to write something out) for my inquiry group. It was simply a sample reflection (and it was the only video reflection I did all year as I prefer to write) but the story I mentioned is the one I ended up describing in this blog. This youtube clip is just a video version of the above post (just trying to differentiate the delivery :-). I have full permission from the student to use this clip.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)